The new world came for me in August of 2023. At the time I was working as the trail crew leader for a National Forest in the Washington Cascades, and life was good. For the last four years, I’d been on the time-honored career path of the seasonal trail worker working his way up to a permanent job. One day in the ranger station, the dream came true. My bosses approached me about a year-round position that would open up in the fall. It was mine if I wanted it, they said.

Until that moment, my career in trails had been something of a gamble. In my twenties I’d bounced between desperate temp gigs and night jobs, plus a few half-baked creative ventures. In all those years of failure, the only things I’d ever had success at were my athletic pursuits: first as a college athlete, and then in the freer world of hiking, climbing and backpacking. All I was ever good for, it seemed, was staring at trees and pushing my body to exhaustion.

That had changed four years earlier, when I accepted a spectacularly low-paying job building trails for a conservation corps in Montana. The deal they offered was simple: if I could hike, do backbreaking labor, and survive on the slim salary—my specialties—they would prepare me for a career on federal public lands. It worked out. After that first season in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, I spent the three best years of my life as a backcountry trail crew leader in the Forest Service. I earned promotions; I became a leader and mentor; I found a path and a career that I loved. I wasn’t just digging dirt and sawing trees—I was the public’s servant out on the land, greeting visitors, giving directions, watching for spot fires, treating kids with heat stroke and evacuating old men off the mountains. I was good at it. By the time I got the offer in Washington, that career had morphed into a purpose, a way for me to exist in the world. After so many lost years, I knew what a difficult thing that was to find. When I got sick, I learned it was an even harder thing to lose.

/~

In mid-August, right after a hard backcountry hitch, I flew home to New England for a family reunion. I woke up the next morning with excruciating muscle aches all down my lower body. It was unlike any muscle soreness I’d ever experienced—at first I thought it was rhabdo—so I went to an urgent care. The doctors were flummoxed, but they ran a COVID test as a formality. It was positive.

I’d never had COVID before—backcountry work is good quarantine I guess. In any case, the infection was mild. I had a cough and a sore throat for about a week, and that was it. When my test turned negative, I flew back to Washington.

I remember chalking up my tiredness in the airport to the red-eye flight. I collapsed in bed at 4 in the morning and woke up in my spartan seasonal-worker bedroom at 4pm the next day. The room was a chaotic mess of unpacked post-hitch clothing and gear, so the first thing I did was try to tidy up a little. I stood up, picked up a shirt, and immediately felt so dizzy that I had to lie down on the floor.

In the weeks that followed, my life rapidly collapsed. Everything from checking email to walking to my kitchen made my head spin. I cashed in a few years’ worth of unused sick time while I waited, patiently at first, to feel better. One day, after seeing if a little yoga would help the brain fog, a new symptom appeared: burning sensations all over my arms and legs, like pins and needles dipped in acid. It lasted for days. When I tried to take a short walk a few days later, the burning pain came back.

By September, it was clear something was very wrong. As the weeks wore on, I spent night after night desperately trying to make sense of what was happening to me. In my windows I could see the new snow accumulating on the gigantic mountains guarding Snoqualmie Pass. I begged these impromptu deities for answers. Why me? What did I do to deserve this? Prone and confined to my dark bedroom, I felt banished. At the end of the season, my bosses checked in about the job offer. In my weak state, I had to turn it down. When my lease in the seasonal house ended, my dad flew out to drive me and my car back east to live with him and my mom. Before we left, he had to pack up my tent and sleeping bag while I watched dizzily in bed, wondering if I’d ever get to unpack them myself again.

/~

By the fall, my doctor in New England confirmed what I’d been afraid of: I had Long COVID. The official diagnosis required twelve weeks of persistent symptoms after the acute infection; I remember hoping right until the last day that they’d magically disappear. Instead, they plateaued. The dizziness had gotten better, but almost any amount of physical exertion resulted in days of burning nerve pain.

I had become, in the grim language of the COVID era, a “long-hauler.” Since 2020, millions of people in America alone had become afflicted by chronic, disabling symptoms after getting COVID, sometimes for years. But medical science was still catching up with the novelty of the illness, and the diagnosis was about all the doctors could offer. Primary care providers as a group still know almost nothing about Long COVID—often less than a layperson would know just from reading the news. They told me to rest, wait, and hope I got better. There was no guarantee I ever would.

The few months that followed are still hard to think about, or write about. There seems to be only one word that can describe it: hell. For someone like me—an athlete, an outdoorsman, an avid reader, thinker, talker—Long COVID felt as if it had been purposely designed for torture. The nerve pain every time I tried to ease back into a light workout was bad enough. But worse than the pain was the grief.

The scale of what I’d lost seemed unimaginable—not just my career, my days in the wilderness, or my purpose in life, but my feeling of belonging in the world. Seasonal work teaches you the importance of having a place where you belong: a home. My home, I realized, had always been my body. My body, more than a vessel for my mind and spirit, or a tool for physical achievement, was more like the medium through which I had always come to know the world, a language deeper and truer than words. Even living again in the house where I’d grown up, with my parents and brothers, could not replace that.

Meanwhile, my new surroundings offered little comfort. Everything I owned from my clothes to my books traced back to the life I’d lost in the outdoors. Nor did it take much imagination to see all the other things that were suddenly out of reach: singing my heart out on guitar, carefree nights with friends, dating, etc., etc. Daily panic attacks raged until my tired body could panic no more. Did you know that COVID can often cause the onset of severe depression? I battled blackness and oblivion night after night, begging my parents for help they could not give. Simply put, I wanted to die. The prospect of living without that purpose felt worse than empty. It felt impossible.

/~

I was at my lowest point when I met the first doctor who understood my condition. By 2024, researchers studying COVID closely had begun to recognize the need for specific care centers for the millions of people—currently estimated at 400 million—who have been disabled by the COVID pandemic. My appointment was with my home state’s first Long COVID specialty clinic.

By then, I’d seen enough baffled doctors to temper my expectations. But this one recognized my symptoms at once, and she gave them a name: post-exertional malaise. The understatement of the century, I thought. But it was a common symptom of many of her long-hauler patients, right down to the burning nerve pain. Her calm, confident explanation nearly moved me to tears.

While scientists still didn’t know what caused PEM, she said, there was one treatment method that showed some promise for long haulers like me. It was called pacing—another understatement. The idea behind pacing was to find the level of activity that triggered my PEM. If I could find that threshold, what she called my “baseline,” I could possibly give my body time to heal whatever was causing my PEM. She told me that with pacing—and we’re talking in the weeks to months range—many of her patients were able to gradually tolerate more and more activity. Their baselines grew. But the key was to avoid triggering the onset of symptoms at all costs. Many people with Long COVID had gotten through the acute stage of illness with only mild post-COVID symptoms, but became severely disabled in the months that followed as they tried to push through the lingering pain and fatigue. The more they struggled to go back to normal, the worse they got—some permanently. If I wanted to get better, I had to do everything possible to avoid getting worse.

By that point, I really was crying. The doctor told me to track everything I did and every symptom I felt relentlessly in a journal. She suggested walking distance as a metric of activity. Back at home, I grabbed my forgotten Garmin watch out of its dusty drawer. From then on, every step I made would be tracked, recorded and analyzed. Every symptoms from acid-burning skin to a slight heaviness in my brow would be captured and described.

The first few weeks were a process of trial and error, mostly resulting in PEM. After each flare-up, I consulted my notes, trying to identify the specific activities that triggered it. I invented a series of symbols to write on my calendar to show flare-ups, mileage, and good days so I could see the trend over time. The heinous delay of PEM, which could strike suddenly up to 48 hours after the aggravating activity, nearly caused me to abandon the whole endeavor. Then, in early January, I had my first long-haul week ever with no PEM at all. I wrote my new baseline in the calendar margins with a frantic hand and a blizzard of underlines. Daily mileage: zero-point-two.

/~

I wish I could say that the rest was smooth sailing, but learning to pace myself was almost as hard as the weeks in bed. Pacing was unlike any kind of training I’d ever done—in fact the goal was that it wouldn’t feel like training at all. It was supposed to be so easy that even my PEM wouldn’t notice it.

But over time, what had once felt like senseless bodily chaos started to become familiar. I began to notice the stages of the onset of PEM—the hot, flushed feeling in my skin just before the burning started, the mottled color my hands turned when I brushed up against my baseline. With still no medical explanation for why any of this happened, I had to develop my own knowledge of my Long COVID—a kind of folk knowledge, obtained through careful noticing, and adherence to its cycles. After months of vicious conflict, my body and I were negotiating a delicate truce. I had to learn to trust it again. In a strange way I knew it was learning to trust me again too.

By springtime, my mileage was up to zero-point-four. I’d started to experiment with different walking schedules, such as taking a longer walk one day and resting completely the next. One day after an entire week of rest I managed to complete a haltingly slow mile-long hike on a local trail. After so much time indoors, I should have been overjoyed. But to be honest, I was as depressed as ever. I was glad to be outside again, but returning to the woods also meant confronting my body’s new limitations in a realer way than before. The familiarity of the trail threw my new life into even starker relief. My mind, not to mention my calves and quads, remembered perfectly the pace and pressure of a 20-degree trail grade, a step over a rock staircase. Often it was all too easy in the moment to scorn my pacing with a fast charge up a hill that I knew could make me bedbound again a day or two later.

Ultimately—and no differently than the millions of people who refused to mask, refused to vaccinate, refused to protect others from my newly-acquired disabling illness—I still could not accept the new, post-COVID world. A few weeks of successful pacing provided just enough illusion to let me think it had all been a bad dream, no matter how many times I paid the price.

/~

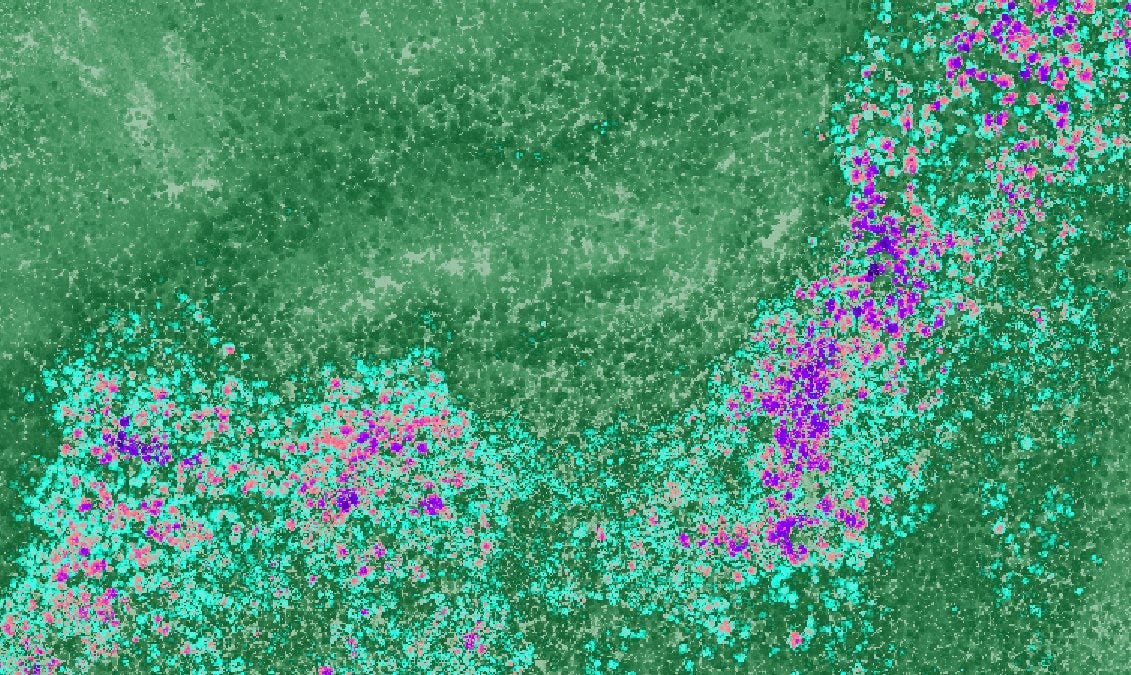

I needed a new perspective, a view of a different world. One day, resting off what had become a rare bout of PEM, I decided to poke around on the GIS program I’d used for work projects. I’d gotten into some online forums where people used satellite data to hunt for big trees. I wasn’t great at tech, but I decided to figure out how to do it myself.

The first time I made a canopy height model—basically a map of the heights of trees—I had a feeling of déjà vu nearly as strong as the smell of my old chainsaw. The pixels in shades of green and pink showed the billowing crowns of trees sprawling across the hillshade of my local hiking areas. It felt like standing beneath the green canopy on a trail hitch; it felt as novel and exciting as the first hike up a new trail. To my surprise, there were some huge trees right in my hometown. A quick distance measurement put many of them well within my baseline.

Through that spring, virtually all my pacing walks were spent hunting for big trees. After one of my first trips, I posted a photo online of me standing next to a giant eastern hemlock trunk, wearing my forest service jacket and work boots. A friend commented, “nice to see you in your element”—understatement of the century.

Finding these trees in the woods was unlike the kind of outdoor adventures I used to pursue. But the sense of discovery was almost greater. These trips took me off-trail, into the kinds of beautiful, unseen corners of the forest that trail work had so often brought me to, the secret waters of a hidden vernal pool, a bed of wildflowers behind a fallen tree. My meandering and backtracking through the woods often confused my Garmin watch, corrupting my meticulous mileage data, but the slow pace of exploration helped ease the stress on my body. At times, I suspected the forest was helping me—calming my nerves, forgiving my trespasses. Walking slowly through the understory, the mosses, and the birdsong was its own kind of healing. I began to learn to find wildness outside of the great wilderness landscapes I’d known—not quite wilderness, but its essential elements that are at home everywhere. And there I was, moving among them in the blossoming canopy. Moving, again, with purpose.

/~

A saying I hear often in the communities of long-haulers like me is that recovery is not a straight line. Over the past year, there have been as many ups and downs as a canopy height model. In May, my average miles per week climbed to one-point-zero for the first time. Then, out of nowhere, I had a flare-up that lasted nearly a whole month. After many long, terrified weeks, it passed as mysteriously as it had come.

In the middle of that first summer, I took a long trip to see friends from my bygone trail days. In Tennessee, my comrade Ralph and I swam in the crystal pools of mountain streams in the Smokies that teemed with life—wildness’s essentials. A week later I went to Montana, saw my trail buddy get married, met a girl, fell in love. On the way home, in Colorado, I learned another one of my closest trail comrades could not seem to accept my new world, and our friendship ended. Along the way I visited old trailheads where I’d packed for sixteen-mile hike-ins, eight-day backcountry hitches, treacherous river crossings in the Winds and Absarokas. I swam in cold rivers that soothed my nerves. I lingered in the fertile lowlands, the beautiful places I’d once departed so hastily.

Acceptance has proved harder to find than wildness. As I write this—five years since the official start of the global pandemic, and a year and seven months since the pandemic destroyed my old world—my body and mind still face daily challenges. The depression and despair has mostly subsided, and my flare-ups seem to be both less frequent and less painful than before. They still find me in my harder moments, usually together. I thank my woodland gods every day for the gift of pacing, for the gifts of wildness and healing, even though no one knows if any of us touched by the pandemic will ever fully heal.

Last September, around my new lousy anniversary, I finally unpacked my long-neglected backpacking tent. I taught myself on GIS how to find lengths of trail systems that were within my baseline for steepness, elevation and distance. My brother and I celebrated my first backpacking trip of my illness on the Appalachian Trail in our native Connecticut. (Two-day mileage: two-point-four.) All along the trail we saw dozens of American chestnut saplings, some nearly full trees, still struggling against their own disabling pandemic a century before. On our next backpacking overnight, in October, we saw hemlocks dead and dying from the adelgid. I saw mountains of disfigured beech trees—beech bark disease—on my first solo backpacking trip, on Vermont’s Long Trail, in an unseasonably warm November. Each journey in the woods shows me more of our new world. It is a world defined by disability, an age of disabled ecologies. Sometimes I think that no one can truly know this world until it arrives for them, but it is already here.

Incredibly beautiful writing, per usual -"a girl"

What a powerful essay. I’m so sorry for all you’ve been through and continue to face. Your story certainly puts my run-stopping injury, which eventually healed, into perspective.