When I worked on the White Mountain National Forest, there were times on patrol when I saw the North Woods transform before my eyes. It usually happened under the spell of the morning or the evening, when the light drew color from the rocks and the leaves that no camera can see, and the shimmering air turned the trees into a hall of portals to distant lands, no two of them the same. I always believed that trail work brought me close to something mysterious and vital in the forest—something that wished to be known and understood, but only on its own terms. In Wyoming it had been a face, and in Washington a voice, but in the forests of the White Mountains what it felt like most was a story, or possibly a dream.

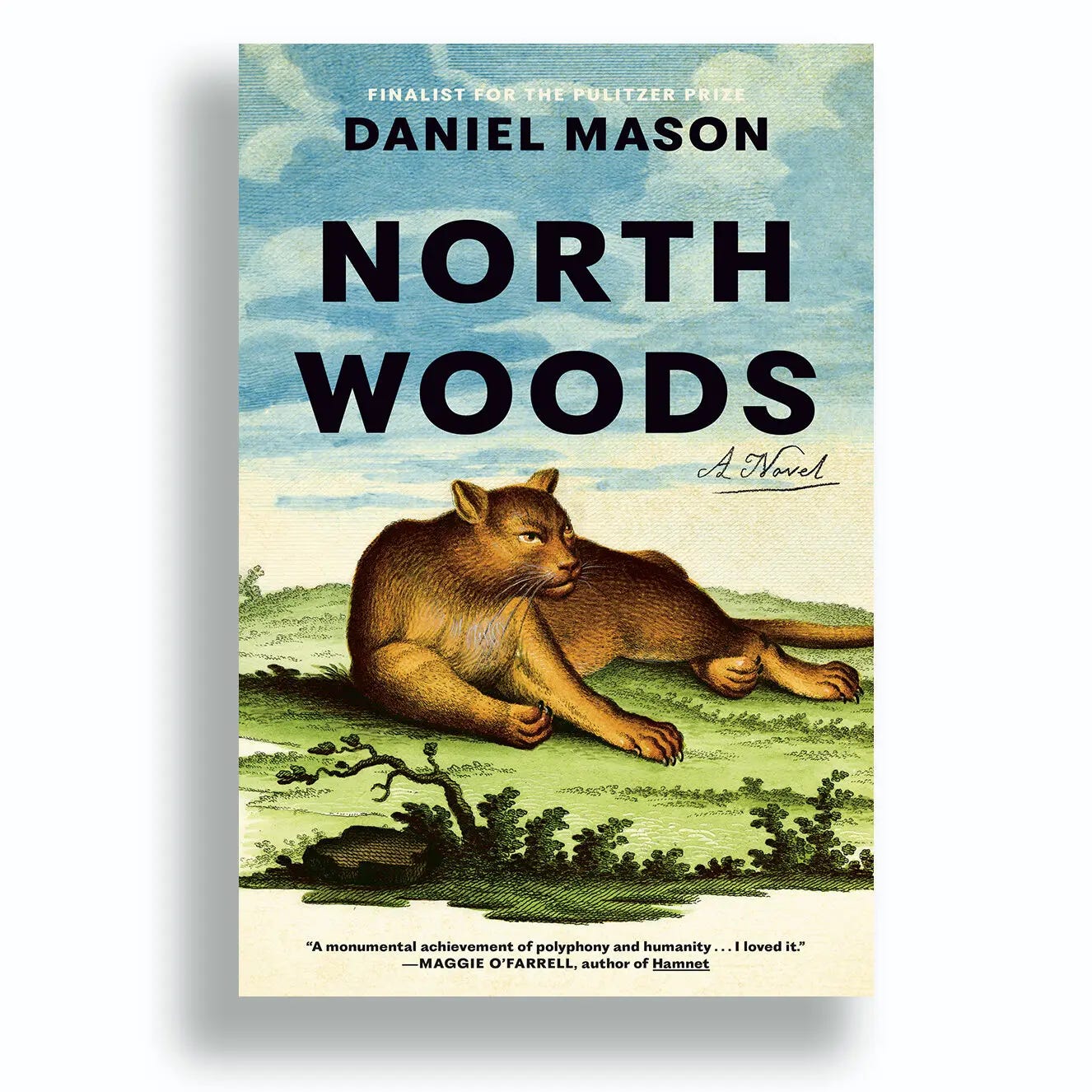

I thought I saw that dreamlike forest again in the opening chapter of North Woods by Daniel Mason. Somewhere in the murky past of Puritan New England, a pair of lovers flees the strictures of their colonial lives into the teeming, prelapsarian woods beyond the old frontier:

They ran. In open fields, they hid within the shadows of the bird flocks, and in the rivers below the silver veil of fish. Their soles peeled from their shoes. They bound them with their rags, with bark, then lost them in the sucking fens. Barefoot they ran through the forest, and in the sheltered, sappy bowers, when they thought they were alone, he drew splinters from her feet. They were young and they could run for hours, and June had blessed them with her berries, her untended farmer’s carts.

Most people I’ve met who love America’s woods in east or west would kill to see what these fleeing lovers saw—the unspoiled continent, the land before our time. Many of us certainly fling ourselves into the wilderness in the hope of seeing at least some broken shard of this original picture, some consolation for the sorry century in which we were born. But for those looking to make a literary escape, North Woods indulges few such follies. The novel is not a portrait of a bygone past, but of its succession—the relentless change of the landscape in our time, and the footprints of history that endure in spite of it.

North Woods follows a succession of characters through the history of a single plot of rugged, inconveniently situated forest in Western Massachusetts. (Is this truly the “north woods”? I don’t recall ever reading the word “spruce,” but I guess it’s all relative.) As the novel’s characters give way through the decades and centuries, the true protagonist turns out to be the rickety house built long ago at the end of the last dirt road. Anyone who’s gone deep into the Berkshires will recall a similar place from their own travels—some ludicrously sketchy car-trail that makes one wonder, why in the hell…? Practically nowhere in New England was too rough for our early settlers, few groves too secret to put to work.

Depending on your outlook, the ubiquitous human history of the northeastern woods can be kind of depressing. Our globe-circling network of stone walls is interesting enough, but other ecological legacies of American settlement, like the missing chestnuts, are harder to stomach. I’ve been a student of New England’s natural history for most of my adult life, and I found myself anticipating the well-known milestones of degradation and loss throughout the book: the clearing of the forests, the poisoning of the rivers, the lost passenger pigeons, wolves, beavers, and catamounts (or are they?), and more. The book follows this history all the way to the present, as drought, flood, heat, and invasive pests wreak more havoc on the land, paradoxically sending even more humans to the edge of the forests. Plus ça change.

But our forest’s long history holds more redemptive stories too. One of our region’s best legacies is the support it gave to the cause of abolition, and especially to slaves escaping north on the Underground Railroad. The rugged hills and forests contributed along with its settlers to foil the despicable profession of the hired slave-hunters, and North Woods reserves its most gratifying payoff for this dramatic story. As the novel rolls towards the modern day’s so-called progress, the woodsy, small-town way of life in this corner of the Berkshires remains remarkably intact. The resilient forest provides a late haven not only for the creatures of the woods, but the people who find inspiration, beauty, and redemption within it—the ones throughout history who’ve sought to know it on its own terms.

Unstated by the novel explicitly, but present nonetheless, is the miracle inherent in the very title North Woods: the regrowth of our forests after being almost completely cleared for agriculture. A careful student of the New England woods will find this in the book’s detailed descriptions of forest history sleuthing, particularly from its consultation with Tom Wessels’s Reading the Forested Landscape, a necessary guide for any northeastern hiker. In fact, I was struck by so many synchronicities between North Woods and my own recent readings—a fictionalized version of Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast, scenes excavated from William Cronon, and more—that I could barely believe it when I found out that Mason was born and raised in California, and not a lifelong student of the Northeast woods like myself.

On a personal level, this was the most rewarding takeaway from North Woods: that the forests of New England tell a story that is not merely of historical value, but one that is vital to understanding our current crisis as a country and a species. As North Woods puts it, the only consolation for a story of loss may be a story of change. New England is a land defined in all times and places by change: the seasons, the mixed, rapid patterns of ecological succession, the waves of people and ecosystems that have spread across it since the Ice Age glaciers retreated, and now the climate changing more rapidly than almost anywhere else. For years I’ve tried to get this through the heads of most of my trail comrades, wonderful, good people, but perhaps hopelessly enthralled by the crisp, golden clarity of the spectacular American West. Here, it is very different. Our woods are ancient, messy, haunted; leafy, vernal, brand new; as crooked and mad as a sorcerer, and as plain as a flannel shirt. They have a story to tell, if we are willing to listen.

"It usually happened under the spell of the morning or the evening, when the light drew color from the rocks and the leaves that no camera can see, and the shimmering air turned the trees into a hall of portals to distant lands, no two of them the same. " - I felt these sentences deeply. From my time hiking the AT in 2010, I still look at the few photos I ended up taking that might have tried to capture some of this and wish I could experience it again and again. I love our southern forests but there is something distinctly portal-ish about the north woods.

Sounds like a good read. Have you read the other "North Woods" by Peter Marchand? I'm thinking you would like it.