The forest either hates trails or loves trail workers. Either way, the trail is where it likes to make its trees fall. I’ve cut trees out of the trail that stood alone in the middle of a spacious meadow that could have fallen in any one of 360 degrees of space, but chose to throw its densest tangle of limbs right over the only two-foot-wide corridor of National Forest land that my crew and I were responsible for. God damn trees, I’d think, while also thanking them for the hiking break. And for the work. The saw practice. The thankless, beautiful job.

From a manager’s perspective, trail work is a fight against entropy. Trees fall, shrubs grow, and soil erodes to ruin the trail constantly, endlessly, forever. The forest, I think, disagrees. It wants the bare soil of the tread to bloom, for flowers and saplings to rise from untrodden ground, for water to pool and soil to settle behind the wild waterbars of fallen trees. The chaotic burst of life that creeps into a neglected trail is hardly entropy, though it makes for slower travel. The most hardcore trail users will find their way regardless: deer and elk, bear and fox, ambling dusky grouse. Even a trail manager can appreciate the wandering game trails that braid the meadows and understories of the woods. More trails; less use. Now there’s a management strategy.

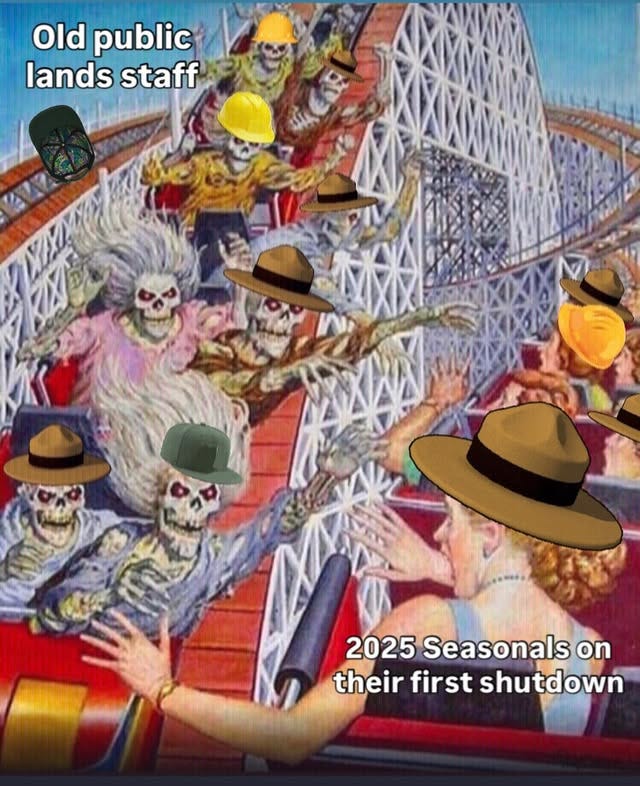

So perhaps the interruption of trail work during the current government shutdown is not all bad. Yet the closures and furloughs at the federal land management agencies this week will undoubtedly threaten our public lands with devastating, possibly irreversible impacts. During the last shutdown, in 2018, a few psychopaths took the occasion to deface petroglyphs in Big Bend, defecate on Death Valley, and cut down Joshua trees in Joshua Tree. Ask yourself: are we, as a country, any saner or less destructive in 2025? I often wonder where those vandals are now, and then I remember they’re in office.

Still, the news of the government shutdown hits differently as a former Forest Service worker: unremarkably. While writing this piece I recalled my own trail season when a looming shutdown hung over our heads for weeks, and our bosses advised us to make backup plans in case we were let go in October. Oddly I couldn’t remember which season it was. Turns out it was all of them.

What do we make of the fact that a government shutdown has become a rite of passage for federal agency workers today? Perhaps we can take pride in the fact that it seems to be yet another instance of American exceptionalism: shutdowns like this do not happen in other nominal democracies, let alone regularly. Yet Americans also seem uniquely content to go about their lives, business, and travel plans while their government wreaks havoc around them. Elsewhere, this kind of ineptitude simply does not fly.

The saddest part, to me, is that the public lands workers so familiar with these disruptions to their work and livelihoods have almost no experience with their agencies working at full capacity. The Forest Service has half of the staff today that it had in 1990; the National Park Service budget has stayed almost the same in real dollars since 1980, despite a 50 percent increase in visitors over that span. This bad historical timing is the latest shutdown’s greatest danger. I don’t know what, if anything, to do about the people killing Joshua trees and off-roading around locked entrance gates, but I do know our public lands are already on life support. Let us instead send the four-wheelers and ATVs after our elected officials until they not only reopen the parks, but fund and staff them at an extravagant level in perpetuity. With our track record, it is the responsible thing to do. A trail or campground left alone can take care of itself. We’re the ones who need some management.

Thanks for reading. By the way, I’m having a sale on annual subscriptions: a year for just $15. My newsletter is already free, but subscriptions help me keep doing this while I look for a job and gulp down coffee. Link to the special offer here.